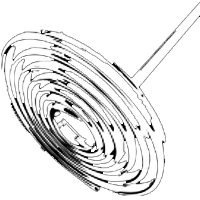

Bee colony

Honey bee colonies are often referred to as superorganisms. This is because each individual honey bee is unable to live alone or do much to support itself, but as a group they are oble to organise themselves to behave as a single, highly effective organism.

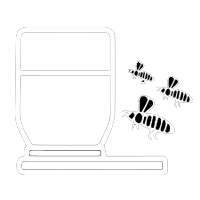

- Adult bees leave the hive to find and bring back food.

- They collect for all the needs of the hive and not just their own requirements.

- Inside the hive the young bees move around and collect debris or dead bees to keep the hive clean and free of inherent disease.

- Guard bees will stop invaders entering the hive and robbing its content.

- Young bees and the queen produce and feed the young larvae to create new bees.

- The comb in the brood nest accumulates waste matter and locks away diseases.

- The communication in the hive through pheromones and food sharing allows the bees to work together for the benefit of the hive. Adult honey bees will die if they use their stings yet they do sting intruders for the benefit of the hive.

Honey bees, ants, termites and other animals that live in com- munities demonstrate these characteristics. What is interesting is that invariably these communities are dominated by females that have given up the role of procreation to a 'queen' and will work together for the benefit of the community. Individual honey bees are unable live on their own and need to be part of a colony in order to survive. If a honey bee becomes isolated from its parent colony it will try to join another colony by begging entrance to the hive. If it does not find another colony it will die within a few days.

For a colony to survive it must have four components:

- A queen

- Worker bees

- Drones (during the summer months)

- A nest with brood (eggs, larvae and pupae)

If one of these components is missing the colony can become stressed, out of balance and therefore prone to disease and less productive. The workers will try to re-establish the balance as soon as possible by:

- Making a new queen

- Encouraging the queen to lay more eggs

- Encouraging the queen to lay drone eggs

- Creating a new nest or repairing the existing nest

The brood nest is the heart of a colony. Here, new bees are nurtured as eggs and larvae that eventually pupate into adult bees. Unlike many other insects, the larvae in a bees' nest remain in cells and are fed by adult bees. The temperature is raised so that the development time can be shortened. The centre of a bees' nest is kept at a constant 33° to 34°C and with a humidity of about 40 per cent. These are ideal conditions for larval growth.

The queen bee

There is normally only one queen in the colony. She is female and under ideal conditions can live up to five years. She has the same-sized head and thorax as a worker but her abdomen is al-most twice as long and her legs too are longer. The queen's main job is to lay eggs that will develop into new bees. Worker bees feed the queen with brood food. This is a mixture of secretions from the worker mandibular and hypopharyngeal glands sup-plemented with some honey. Brood food produced in glands in the head of worker bees is high in energy and nutritional value. The more the queen is fed, the more eggs she will lay.

In spring and summer when the colony is expanding rapidly the queen may lay up to 2000 eggs in a day. The weight of that vast number of eggs is greater than her bodyweight. She does not really have enough time to feed herself or to digest pollen and nectar (the nnormal food for adult bees). The food fed to the queen by workers has been digested and the proteins have been converted into essential amino acids that the queen can use directly to produce eggs. As the season moves on, the number of eggs laid by the queen diminishes, and in the depth of winter the queen may cease egg laying altogether. As the need for new bees is reduced, the workers cut down the food they give to the queen to reduce her egg-laying capacity.

The queen produces pheromones that control the activities of the workers. One effect of these is to prevent the workers (who are also female) from laying eggs. Another is to let the colony know that there is a queen in the hive. If the queen is removed for any reason the colony will recognise this within 30 minutes and start preparations to produce a new queen.

The pheromones produced by the queen are spread throughout the colony by the workers touching her and then touching other workers. Often, when you are looking out for a queen in a colony she can be seen surrounded by a 'courť of workers who are feeding her, touching her and gently guiding her round the nest to encourage her to lay eggs.

There can be more than one queen in the hive. There is a process called supersedure when a mother and her young daughter will both happily lay eggs as they move around the colony. On other occasions there may be two or more queens raised by the colony but if this occurs the queens will find each other and engage in a fight where one will die. The remaining queen is unhurt and will proceed to lay eggs for the colony.

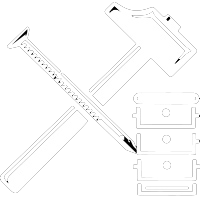

Drones

Drones are male bees. Their primary job is to mate with queens. They are accepted into any colony and seem to move fairly freely about in an area and visit any number of colonies. Drones develop from unfertilised eggs laid by the queen. The workers build the honeycomb cells in the colony. When they do this they are able to determine the size of the cell. Workers' breeding cells are slightly smaller than those used for breeding drones. When a queen lays an egg she will feel the size of the cell with her front legs and antenna. Once she has sensed the size she will reverse into the cell and lay an egg at the base of the cell. If the cell is a large (drone) cell she will leave an unfertilised egg. If it is a smaller (worker) cell she will deposit a few sperm onto the egg just before she lays it. The sperm penetrate the egg lining and fertilise the egg. In this way the workers are able to regulate the ratio of workers to drones in the colony by guiding the queen to lay eggs in cells for workers or drones. Drones are larger than workers and take longer to develop. During the first two days after the egg hatches the workers, will feed the larva with a mixture of secretions from their mandibular and hypopharyngeal glands similar to the feed given to workers. After the two days the workers will start to feed the larva with pollen, honey and a much-reduced feed from their glands. The larva takes seven days to grow to full size and then pupates in its cell for a further 14 days after the workers have capped the cell with a porous mixture of wax and pollen.

When the drone emerges he is fed for a few days with brood food by the worker bees. After that he will then learn to feed himself with pollen and nectar in the nest, but will still beg food from the workers in the hive. He does not fly out to forage for food. After about 10 days he will be sexually mature and able to leave the colony to go out on mating flights in search of virgin queens.

Drones live for about 40 days although this figure will vary with the weather and their level of activity. By the time September comes, all the drones will have been forcibly ejected from the colony by the workers. This is because after this time it is unlikely that the drones will be needed to mate with queens and as food will be scarce in the coming months the colony decides the drones must be sacrificed. Once a drone has been ejected from a hive it will only live for about two days before dying of starvation. The remainder of the colony endures through winter and early spring with no drones.

In late spring in the following year the workers will begin to guide the queen towards the larger drone cells and she will start to lay unfertilised eggs to raise the new season's drones. At the height of summer there may be about 200 drones in a colony although there can be as many as 1000. It appears that when a colony is preparing to swarm there will be more drones produced; in addition, other drones will be attracted to the colony in readiness to mate with any new queen. A colony with a number of drones in it often seems calmer. It has been suggested that, because drones are larger than workers, their presence in the colony helps to regulate the temperature in the nest.

Workers

Workers are sterile female bees. They are produced from a fertilised egg laid by the queen. When the egg hatches, workers will feed the larva a nutritious food from their glands. This food is not as high in sugar or as nutritious as the feed given to queens. After two days the workers will start to give honey and pollen to the larvae. Feeding is done regularly but the larva is not given too much food (as is the case with the queen larva). The result is that the larva takes six days to grow and is not as large as the queen or drone larva. However it is still about 1500 times larger than the original egg when fully grown.

Once the larva has reached its full size, the cell is sealed with a capping of wax and pollen. The larva pupates and remains in the cell for a further 12 days after which the worker cuts her way through the capping to emerge as an adult. In any colony, workers are the most numerous members (up to 60,000 individuals in the summer and down to about 15,000 in winter). The workers do all the work to maintain the colony and live for only about six weeks in summer; in effect they die from hard work. In winter, workers can live up to six months, keeping the queen and themselves warm and being ready to care for new brood once the spring returns and there are plants providing nectar and pollen again.

When a new worker bee emerges she is unable to do many of the tasks in the colony. Her first job is to feed to restore her energy levels. She then starts work cleaning the hive by removing any debris that may have accumulated. As she grows older she is able to do other tasks and in a rough chronological order she will do the following duties:

-

Clean the hive

-

Clean and polish cells

-

Feed larvae

-

Feed the queen

-

Make wax, build honeycomb and seal cells

-

Process and store nectar and honey

-

Guard the colony entrance

and then:

-

Forage for nectar and pollen

-

Forage for water and propolis

During the active season, the first group of tasks is performed in the first three weeks of a worker bee's life and the last two tasks are done during the last three weeks of its life. This has the advantage that bees which have reached the end of their lives normally die whilst on a foraging trip and not inside the hive. Unlike modern humans the worker bee is expected to work to the end of its life and there is no concept of 'retirement'.

The change of the tasks as the worker ages is closely related to the development of the glands of the bee over time. The emergent worker has spent all her energies in pupating and must feed heavily on pollen and nectar so that her body can continue to develop. The first glands that start to work are the hypopha-ryngeal glands in the head of the worker; these produce brood food for the larvae and also food for the queen.

Later, glands on the underside of the abdomen start to

produce wax so that she is able to build cells and repair the nest. Later still

the hypopharyngeal gland evolves further to produce the enzymes needed for the

processing of nectar into honey. Finally the venom and sting glands become

functional and the worker is then able to take on guard duties. The whole

process takes about three weeks in summer and during this time the worker will

remain in the hive for most of the time. Once the worker is fully functional she

is ready to leave the hive, cease being a 'house' bee and become a foraging bee.

Genetic diversity is maintained in the hive as the queen mates with many drones

and some workers appear to be more adept at some tasks than others. Also not all

of the workers carry out all the tasks and, in an emergency, workers can revert

and take on the duties of their younger sisters if required. Although their

roles may seem very clearly defined, in fact worker bees are able to take on

many different tasks during their short lives.

It is popularly believed that workers spend all their lives working for the good

of the colony. Some detailed research has shown that a worker may in fact spend

up to eight hours a day resting (or at least not doing any particular activity).

Whilst the main time for activity is during the day when bees are foraging for

provisions to take back to the hive, bees will continue to work in the hive

overnight.

The brood still requires feeding; the nest must be kept warm and nectar still

needs processing into honey.

Excerpt from the book: The bbka guide to beekeeping